His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), the Fourth Caliph of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, briefly stayed here before emigrating to UK.

Ayesha Mahmood Malik, UK

On a warm April day in 1984, my maternal grandfather was asked to make preparations for a special guest who would be staying at his residence in Rabwah that evening. He was instructed to temporarily release all his domestic staff and seal all windows and doors. While the request may have sounded peculiar, it had been just two days since the passage of Ordinance XX by General Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan, criminalising the very existence of Ahmadis and forbidding them to identify as Muslims. Ahmadi Muslims had already been cast out of the fold of Islam 10 years earlier, this latest Ordinance was an attempt to seal their fate.

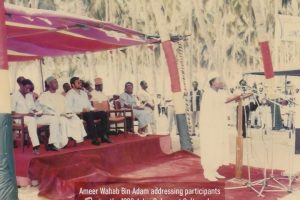

As the clock struck 11pm on 28 April 1984 and my grandparents’ visitor arrived in a small white car, the enormous sensitivity of the occasion began to dawn on them. It was Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (rh), the Head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, who was being forced to migrate from Pakistan due to Ordinance XX and who was to be lodged in my grandparents’ home that night before being driven to Karachi to take his flight to England in the early hours of the following morning. An arrest warrant had been issued for him and since the new legislation forbade Ahmadis to even pose as Muslims, it had become impossible for him to carry out his duties without violating the law.

Thus began a compelling migration from one’s homeland spurred by a fateful catalyst for change: while Ordinance XX proved to be a watershed moment for Ahmadis in Pakistan, exacerbating their suffering and making even everyday actions such as using the Islamic salutation of ‘Assalam-o-Alaikum’ a criminal offence, it prompted the shift of the Community’s headquarters to the UK ushering in a brand-new chapter of growth and prosperity.

Four decades on since its enactment, the Ordinance has ironically served as a precursor to the beginning of new chapters of both progress and persecution. Although intended to make the survival of Ahmadis virtually impossible and stall the Community’s expansion, it became the catalyst for the creation of a new centre for Ahmadi Muslims in the UK and under its divinely-guided leadership, the Community continues to flourish far and wide, having since established its presence in more than 200 countries.

While the persecution of Ahmadi Muslims has touched every sphere of life in Pakistan, Ahmadis have shown great courage, resilience and fortitude in grappling with the challenges borne out of this and have prospered notwithstanding the odds. A recent study undertaken by the Center for Law and Justice observed how Ahmadis in Pakistan despite the difficulties they encounter, are highly educated and have successful careers.

State-sponsored persecution is considered to be the most perilous form of marginalisation inflicted upon religious minorities. When a state persecutes, it transforms into an agent of affliction and abandons its primary role as an agent of protection. Having grown up in Pakistan and having been privy to some of the challenges faced by Ahmadis in the country, there is nothing worse than being persecuted by one’s own people. Yet, as I reflect on those momentous moments of change brought on by a law that was intended to stifle and suffocate, the Community was instead granted a new breath of life – an enduring testament to its Divine origins and a fulfilment of the promise to cause its message to reach the corners of the Earth.

About the Author: Ayesha Mahmood Malik is the Editor of the Law and Human Rights Section of the Review of Religions magazine. She is interested in Law and Religion, in particular Islam and Human Rights, the role of media in crisis reporting, International Human Rights and the import of religion on radicalisation. She has spoken frequently on these issues in the national media and various universities in the UK, including the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics. She is a graduate of Harvard Law School.

Add Comment