The Jewel of Medina by Sherry Jones Beaufort, 358 pp

God’s guidance for mankind was conveyed by the prophets of God. Muslims revere them all, with the most revered being the Holy Prophet Muhammad(saw) who conveyed God’s final Message the Holy Qur’an – the literal Word of God delivered to the Holy Prophet Muhammad(saw). The Hadith contains the practice and sayings of the Holy Prophet(saw).

So when the Word of God or the teachings of any of His Messengers are deliberately distorted as in The Satanic Verses, the film ‘Fitna’ by the Dutch filmmaker Geert Wilders, or the Danish cartoon incident, it is a source of great pain for Muslims. The Jewel of Medina, a work of historical fiction on the life of Hadhrat A’ishah(ra) before, and following, her marriage to the Holy Prophet(saw), is the latest book to have once again wounded Muslim sentiment.

Jones, the author of ‘The Jewel of Medina’ is a journalist based in Spokane, Washington, has described her book as:

‘An entertaining and informative novel about Islam for Western readers, one that might be used as a teaching tool in schools. Even though [The Jewel of Medina] is a work of fiction and there is imagination involved, it’s all rooted in history.’ (Sydney Morning Herald, Joyce Morgan, January 6, 2009)

Scheduled to be published by Random House in May 2008, the book would probably have received little attention, if any, had it not been sent for a review to Denise Spellberg, an associate professor of Islamic history at the University of Texas in Austin. She condemned it for turning ‘sacred history’ into ‘soft-core pornography’ (Nomani 2008).

The contract with the author was cancelled after the company was warned that its publication could incite acts of violence.

The British edition to be published by Gibson Square was delayed following an arson attack on the London home of Martin Rynja, owner of Gibson Square publishing house, in September 2008. The American release date was then rushed forward and The Jewel of Medina was eventually published in the US by Beaufort Books.

The book has been also been criticised by non-Muslim reviewers on account of its poor literary merit. Lorraine Adams (2008) has described Ms Jones as

‘… An inexperienced, untalented author (who) has naively stepped into an intense and deeply sensitive intellectual argument.’

Other comments however, relate to the presentation of the material in the book. (Geraldine Brooks, 2008)

‘There are some facts in these pages, but they’re drowning in a historical and under-researched claptrap. Jones’s ‘A’ishah is portrayed as a bloodthirsty, sword-wielding brat without a profound thought in her head, a would-be warrior forced into marriage with Muhammad when her heart is already set on another, younger man.’

The writer continues:

‘Okay, okay . . . The Jewel of Medina is fiction. Jones is entitled to imagine whatever she wants. But if you wish to claim that your novel is “extensively researched,” why lurch around in time and space, grabbing at concepts such as hatun, or leading wife, which Jones knows full well belongs to the Ottoman empire of centuries later, or purdah, which exists in Persian, Urdu and Hindi but not Arabic? Why refer to an Islamic veil by the modern Western term “wrapper”?’

“We need to speak up for free speech,” Jones says. “There are those extremists of varying beliefs who would like to impose their way of thinking on the rest of the world. It is important for us to be vigilant.” (Sydney Morning Herald, January 6, 2009 )

As mentioned earlier, the authentic and accepted sources of this history are the Holy Qur’an and the hadith. Even then, only those narrations considered to be reliable are accepted as valid. Muslims do not just accord this respect to figures from Islamic history, but extend it to all prophets of God. This is as Denise Spellberg puts it, ‘sacred history.’

So for Ms Jones to be dismayed at the hurt felt by Muslims at the publication of her book is extraordinary. Of course such hurt must never be expressed through violence, but through peaceful and lawful protest.

But let us for the moment, go along with the author’s claim that her desire to write this book was sparked by the 2002 spring invasion of Afghanistan by US troops. After hearing reports of the treatment of women under the Taliban:

‘As a feminist I was disturbed by these reports and I wanted to learn more’. (The Jewel of Medina: Questions and Answers p.355).

How did the author go about learning more about Islam?

‘I read a few books about women in the Middle East by American journalists Geraldine Brooks and Jan Goodwin.’

One wonders why Ms Jones did not consult Islamic scholars if she really wanted to know what Islam really said about the position of women. Therefore, the mind boggles at Ms Jones’ aspiration that:

‘My sweet little historical novel, my epic love story,’ could be a ‘bridge-building book about Islam.’ (Joyce Morgan 2009)

To build bridges one must have common ground and firm foundations. One must select one’s construction materials carefully. Reading a few books on the treatment of women in Muslims countries by Western commentators on Islam does not comprise sturdy construction material.

So what is historical fiction? Historical fiction is a story that takes place during a notable period in history, and usually during a significant event in that period. Historical fiction often presents actual events from the point of view of people living in that time period.

In some historical fiction, famous events appear from points of view not recorded in history, showing historical figures dealing with actual events while depicting them in a way that is not recorded in history.

Now the author claims that her book has been extensively researched. Therefore it is reasonable to expect her to stay close to true events. Sadly this has not been the case and not only has Ms Jones been liberal with her interpretation of history, but she has also distorted key events in Islamic history in her attempt to create a rather fanciful tale involving the most respected and loved personage in Islam and his wives, with special focus on Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra).

How can she hope ‘that it might be used as a teaching tool in schools’ and then write the following account about the Holy Prophet’s(saw) call to Prophethood:

‘Muhammad was sitting in meditation and praying to his family’s gods when a sound like thunder shook the walls’. (p.227)

One is left aghast at Ms Jones’ description of the Holy Prophet(saw) praying to ‘his family gods’! The description will strike a blow at the heart of every Muslim, for Islam absolutely abhors idol worship of all kinds. Islam is a monotheistic faith. Prior to the revelation of Islam, the Holy Prophet(saw) was a monotheist who would go into seclusion to worship.

The Holy Prophet(saw) like Hadhrat Ibrahim(as) before him, had a deep belief in the existence of One God alone. Both prophets vehemently rejected the idol worship of those around them. Both preached the existence of the One God alone bringing themselves into confrontation with all around them. Both refused to compromise the unity of God to please their contemporaries.

Ms Jones writes, in response to a Question and Answer session with her included in the book, that she wanted to write about Muslim women to liberate and empower them.

‘I discovered that the Prophet Muhammad had multiple wives and concubines. Being unable to find out much information about any of them, made me want to tell their stories to the world’. (p.355)

‘At first I just wanted to honour these women by telling their stories. Then during my research I discovered things about Muhammad and Islam that excited me and I began to hope that in writing this book I could help increase intercultural empathy and understanding and that I could empower women especially Muslim women by showing them that Islam is at its source an egalitarian religion’.

One wonders why Ms Jones concluded that she needed to ‘empower Muslims women ‘and show that at source Islam was egalitarian.’

If her desire comes from reading accounts of the treatment of women under the Taliban, then one has to ask how her novel will succeed in empowering Muslim women when those women already have access to the Holy Qur’an which has enshrined the rights of women for all time. It has established their spiritual equality with men (Ch.33:V.36; Ch.4:V.125), and it has established their economic independence (Ch.4:V.33). From the hadith we read that:

Hadhrat Anas(ra) reports that the Holy Prophet(saw) said: ‘The pursuit of knowledge is an incumbent duty placed upon every Muslim man and Muslim woman (Ibn Majah).

Also we read that the Holy Prophet(saw) said: A man who brings up three daughters or three sisters, teaches them good morals, treats them with kindness until they become independent, Allah makes Paradise incumbent for him (Mishkat vol.2).

If after all this knowledge, women are still disempowered, then one cannot blame it on Islam but on their so called ‘Muslim’ societies that are in reality anything but Islamic.

So does her lead character ‘Aisha bint Abi Bakr’ come across as an emancipated woman?

The Jewel of Medina takes as its core story line, the fanciful and erroneous idea that ‘A’ishah(ra) did not initially want to marry the Holy Prophet(saw).

‘Married to Muhammad! It couldn’t be. He was older than my father’, (The Jewel of Medina, p.26) ‘A’ishah(ra) thinks to herself.

Instead Jones’ character is in love with Safwan ibn al-Mu’attal, a young Makkan that she has been engaged to since childhood. Matters come to a head when she and Safwan make plans to elope after ‘A’ishah has an argument with Muhammad. This forms the starting point of the book. In Islamic history it is recorded as the ‘Incident of Ifk’.

Now Jones readily admits that the historical ‘A’ishah(ra) was not engaged to Safwan (p.357). She provides no evidence either for her belief that Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) was not in favour of her marriage to the Holy Prophet(saw). One wonders therefore why she decided to construct a tale designed to honour Muslim women, where she has a heroine, who is a wife of the Holy Prophet(saw), contemplate adultery, a sin which is abhorred in Islam?

In a written response for the Islam Online Ms Jones comments:

‘…… my book explores what really might have happened in the famous “affair of the necklace,” when Aishah strayed from her caravan, then rode into Medina with another man. According to my research, she was accused of adultery, but a revelation from God declared her free of guilt. My novel too, exonerates Aishah, but only after she has been tempted. In this way she becomes a true heroine, one who learns from her mistakes and matures into a more devoted wife and more devout Muslim.’

The notion that resisting temptation makes one a better person, is a very Christian concept. Ms Jones’ ‘A’ishah(ra) is tempted to engage in an adulterous relationship whereas the historical ‘A’ishah(ra) was not. Why is Ms Jones’ ‘A’ishah(ra) any more of a heroine as a result of this? The reasoning is flawed and has a resonance with Christian concepts of sin and repentance – that through sinning and repentance, one is stronger than the person who refrained from sin.

The Jewel of Medina opens with a distorted account of the incident at Ifk. Ms Jones’ ‘A’ishah(ra) arranges with Safwan to deliberately stay behind while the army moves on. However once with Safwan, she realised the enormity of what she has done and changes her mind. Safwan too, has a change of heart. The couple then goes back to Madinah and ‘A’ishah(ra) invents a tale about having lost her necklace. However, as she enters Madinah, word has got around of the incident and people shout out ‘Adulteress!’ at her. The Prophet asks her to return home while he considers what has happened. Whilst at her parents’ home the Prophet visits and has a revelation which clears A’ishah’s name.

Now this account is not just a case of historical license but a breathtaking distortion of history itself! History has preserved Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) own account of the incident. There was no relationship with Safwan(ra). However the Incident of Ifk did occur as she was returning home with the Holy Prophet(saw) and the Muslim army from a journey. The army had made camp but then decided to move on. Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) realised that her necklace had disappeared and so she went to search for it. Meanwhile, the people appointed to lift her palanquin set it atop the camel thinking that she was sitting inside it. They then set off with the rest of the army. As she was very slight at the time, the lightness of the palanquin did not make the lifters suspect anything.

Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) reports that on her return, having found the necklace, she became very distraught that the army had gone and the field lay empty. However, she decided that it would be better to stay there, because she felt assured that as soon as her absence was noted, the convoy would return to look for her. So she stayed and eventually fell asleep. It happened that a Companion by the name of Safwan Bin Muattal(ra) who had been appointed to follow on at the rear of the army reached the place where Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra)) was resting. He immediately recognised her because he had seen her before the commandments of Pardah had been promulgated. He then led the camel with Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) on top of it back to the spot where the Islamic army had been encamped.

On arrival at Madinah, Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) became ill and it was during the period of her illness that rumours and allegations about her were spread. After a while she came to know of the accusations. She then decided to go to her father’s house. It was while she was here that the matter was resolved when the Holy Prophet(saw) received a revelation proclaiming her innocence (Seerat Khatamun-nabiyyin).

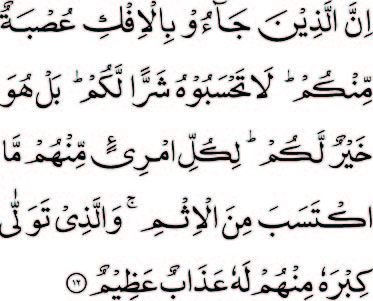

The verse revealed (Ch.24:V.12) is very significant because it lays down the guidance of four eyewitnesses being needed when accusations of adultery are made against people.

One wonders therefore why Ms Jones has her character ‘A’ishah tell the reader:

‘Centuries later scandal still haunts my name. Where you are, mothers chastise their daughters with a single name. “You Aisha!” they cry, and the girls turn away in shame.’

She adds, addressing possibly the extremist mullahs of today:

‘The girls turn away because they don’t know the truth; That Muhammad wanted to give us freedom but that the other men took it away.’

But then unbelievably she writes:

‘Allah willing, my name will regain its meaning. No longer, then, a word synonymous with treachery and shame.’ (p.10)

One wonders aghast, which books Ms Jones has been reading to ever infer that the name ‘A’ishah is not respected by Muslims. How many books of Islamic history can she have used for her research not to know that this is one of the most popular of Muslim girls’ names?

Reviewers of The Jewel of Medina have noted that Ms Jones does not follow the usual western path of criticising the Prophet(saw) for the age difference between him and Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra). She also makes her older than Muslim commentators suggest she was, at the time of the consummation of her marriage. However interestingly, whilst not directly taking issue with the age of Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) at marriage, throughout the book the reader is never allowed to forget her age with constant references to her as ‘the child bride’ by all the main characters. The implication however, whilst not discussed, is that there is something abnormal.

Muslims readily acknowledge the age difference between the Holy Prophet(saw) and Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra). Records suggest that her nikah took place at age 9 and the marriage was consummated when she was aged 12 years (Seerat Khatamun-nabiyyin). However marriage at a young age was not uncommon during these times. Indeed there is nothing recorded about her having any regrets about the marriage and evidence that she fully consented to it.

Records indicate that Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) was renowned for her intelligence, and learning and knowledge. A very large and essential portion of the traditions of the Holy Prophet(saw) comprise of the reports of Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra). They add up to some 2210 traditions. Her knowledge, wisdom and expertise in matters of Islamic jurisprudence was such that imminent scholars acknowledged her superiority and expertise, and would strive to profit from it. It is even recorded in the traditions that after the Holy Prophet(saw) passed away, there was never any doctrinal complication whose solution could not be found with Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra).1

Ms Jones needs to reflect, who is the more emancipated; the historical Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) who loved the Holy Prophet(saw), and who is revered in Islamic history as a women who taught the faith to the companions of the prophet, or Ms Jones’ ‘A’ishah who is portrayed as a tempestuous teenager, jealous of the other wives and frequently upsetting them.

About the Holy Prophet(saw) she writes:

‘From what I have read he was fairly egalitarian in his attitudes towards women. Of course nearly all his wives and concubines were supposedly very beautiful which tells me he might have had personal reasons for marriage too.’

How interesting given her earlier statement that:

‘Being unable to find out much information about any of them, made me want to tell their stories to the world.’ One wonders how Ms Jones knew therefore, that his wives were ‘supposedly beautiful’.

It is curious also that Ms Jones devotes only a few lines in passing to Hadhrat Khadijah(ra). Herein surely lies one of the greatest tales of female empowerment and of a marriage based on deep love and affection. She was forty when she proposed to the Holy Prophet(saw) who was only 25 years old. On marriage, with her consent she handed over all her slaves to him whom he promptly liberated. She gave up a life of wealth and privilege for him and was the first female convert to Islam when he received his calling. He never married in her lifetime and it was only after her death that he married other wives. His love for her remained after her death and it is reported that Hadhrat ‘A’ishah(ra) said:

‘…Never did I feel jealous of the wives of Allah’s Apostle (May peace be upon him) but in case of Khadija, although I did not (have the privilege to) see her.’

She further added that whenever Allah’s Messenger(saw) slaughtered a sheep, he said: ‘Send it to the companions of Khadija.’ I annoyed him one day and said: ‘It is Khadija only who always prevails upon your mind.’ Thereupon Allah’s Messenger(saw) said: ‘Her love had been nurtured in my heart by Allah Himself.’ (Sahih Muslim)

Now this alone is a message for the modern western woman living in a society where a woman’s worth is still judged largely on her beauty and youth.

Islam has given special status to the institution of marriage. Illicit relationships are expressly forbidden thus ensuring that women are respected and given their due rights.

The Holy Prophet(saw) never had any concubines. Yet Ms Jones describes her character Maryam as one of the prophet’s concubines. One can infer that she is alluding here to the historical character, Mariyah Al-Qibtiyyah(ra) who in reality came from a high class family. Mariyah was presented in marriage to the Holy Prophet(saw) by Muqauqis the Coptic ruler of Egypt,and on her way to Madinah had converted to Islam. She bore the Holy Prophet(saw) a son who was named Ibrahim.

However Ms Jones, in her desire to empower women, describes her as the Holy Prophet’s mistress from whom he has his son Ibrahim. In The Jewel of Medina, Muhammad never marries Maryam who in turn does not convert to Islam. We are reminded of this when Ms Jones describes Maryam’s home: ‘A tapestry on the wall depicted a haloed Virgin Mary on an ass’ (p.311).

The Holy Prophet(saw) never had any concubines nor did he keep any female slaves for that purpose. Indeed upon his marriage to his first wife Hadhrat Khadijah(ra) he released all her slaves. This was before he had received any commandment from God that he was His Prophet and Messenger. Why then would he accept in marriage any woman who had not freely consented to marry him?

Let us remind ourselves of the objectives that were attached to the marriages of the Holy Prophet(saw). According to Islam, the purpose of marriage is for the creation of progeny, the expansion of relations of love and compassion and the care of orphans and widows. In addition to these general objectives, Holy Prophet’s(saw) marriages served other purposes as well.

Firstly, he wanted to remove certain primitive customs and erroneous beliefs, and secondly to instruct women in matters of Islamic Shariah so that other Muslim women should be educated and trained through them.

The fact that the Holy Prophet’s(saw) marriages were not a result of personal desires and were for religious reason is clear. Some of the women he married were of an age where they could not bear any children. For instance Hadhrat Umm Salamah(ra) was previously married to Abu Salamah bin ‘Abdil Asad(ra) who was a very devout Companion and had accepted Islam in the early days. After his death, the Holy Prophet(saw) proposed to her because she was endowed with such personal qualities as made her suitable to be a wife of a law-bearing prophet. She was also the widow of a venerable Companion of great stature. Furthermore, she had children and it was important that she was well cared for. Apart from being extremely intelligent and virtuous Hadhrat Umm Salamah(ra) was a lady of great stature, sincerity and a staunch belief in Islam. She was first among the ladies who took part in the migration to Madinah. Hadhrat Umm Salamah(ra) knew how to read and write as well. She played a highly significant role in the religious education and training of Muslim women. Many Traditions and accounts have been reported by her. Interestingly, she was 38 years old when the Holy Prophet(saw) married her, which according to the culture of the time was considered to be advanced middle age.

Hadhrat Juwairiyyah(ra) (Barrah) was the daughter of Harith Bin Zarar,(ra) chief of the tribe of Banu Mustaliq. She was married to Musafi’ Bin Safwan who had been killed in during a battle with the Bani Mustaliq. According to the custom, these prisoners were distributed by the Holy Prophet(saw) among his Companions. This distribution resulted in Barrah Bint Harith to be given into the care of an Ansari Companion by the name of Thabit Bin Qais. In order to attain her freedom, Barrah made a request of manumission to Thabit Bin Qais. According to this if she were to pay a certain amount of money to him as ransom she would be granted her freedom. She then had an audience with the Holy Prophet(saw) and reminded him that as she was the daughter of a chief of Banu Mustaliq, she requested his assistance in payment of the ransom. The Holy Prophet(saw) decided to free her and then sent her a proposal of marriage.

When she accepted, he personally paid her ransom and married her. The Companions, observing that the Holy Prophet(saw) had granted the daughter of the chief of Banu Mustaliq the honour of matrimony, considered any continued enslavement of his in-laws to be disrespectful. Therefore, one hundred families consisting of hundreds of prisoners of war were freed all at once without any ransom payment.

This marriage and this favour resulted in the people of Banu Mustaliq becoming very impressed with the teachings of Islam and became devotees of the Holy Prophet(saw).

Another account states that Juwairiyyah’s father requested an audience with the Holy Prophet(saw) and stated that as he was a chief of his people, his daughter could not be kept imprisoned in such fashion. Upon this, the Holy Prophet(saw) replied that Juwairiyyah should be asked to decide whether she wanted to be free and return or whether she wished to stay, and that her wish would be honoured. When the question was put to Juwairiyyah she expressed her preference to stay near the Holy Prophet(saw) and to become Muslim. At this, the Holy Prophet(saw) freed her and then married her.

Thus the Holy Prophet’s marriages laid down the foundation for the objectives of marriage. Islam has permitted marriage to divorcées; it has laid down guidance about the treatment of female prisoners of war and urged that widows especially those with children should be remarried. It has also removed ageist barriers to marriage that we still see in operation in society today.

For the Arabs at the time of the Holy Prophet’s(saw) advent his marriages served to end existing prohibitions against marriage. This was illustrated when the Holy Prophet(saw) married Hadhrat Zainab(ra).

Along with a number of anti-Muslim writers, Ms Jones devotes a lot of attention to this marriage. She introduces the issue with her character ‘A’ishah hearing women gossip in the market place about her character Zaynab, answering the door to the Holy Prophet(saw) wearing only a nightgown. This is then followed by lurid description of the Prophet’s reaction and of how Zaynab wants to divorce the Prophet’s adopted son Zayd, so that she can marry him.

Ms Jones takes care to give us the supposed details of Zaynab’s beauty.

‘Zaynab was a lioness, gleaming with power. Her eyes shone a startling gold, like ripe dates fresh form the tree, and her loose dark hair curled wildly about her face vining with her silk green wrapper.’ (p.146)

Ms Jones has Zaynab leave her husband Zayd causing the Prophet(saw) to fret that she is doing so in order to marry him. However that is not possible because Zayd is his adopted son.

The situation is ‘resolved’ when the Prophet receives a revelation giving him permission to marry her. Along with other anti-Muslim writers Sherry Jones introduces a note of cynicism as to convenience of the revelation.

So what were the facts? Hadhrat Zainab(ra) was the daughter of the Holy Prophet’s(saw) paternal aunt, Amima Bin ‘Abdil Muttalib. At the suggestion of the Holy Prophet(saw) Zainab Bint Jahash(ra) married his freed slave and adopted son, Zaid Bin Harithah(ra). It is recorded that initially, Hadhrat Zainab did not agree to the match bearing in mind the distinguished status of her family. However, upon realising that it was the wish of the Holy Prophet(saw) for the marriage to take place, she agreed to the match. Even so, due to differences in their social status the marriage did not work out.

Zaid Bin Harithah(ra) came to see the Holy Prophet(saw) of his own accord and asked for permission to give her a divorce. The Holy Prophet(saw) was grieved at the situation and dissuaded Zaid(ra) from divorcing her. The words of the Holy Prophet(saw) are recorded in the Holy Qur’an

…keep thy wife to thyself and fear Allah… (Ch.33:Vs.38)

The Holy Prophet(saw) disliked divorce in principle. However as the couple could not resolve their differences, Zaid(sra) divorced his wife. When Zainab(ra) completed the probationary period after her divorce (as dictated by Islamic law), the Holy Prophet(saw) received revelation about the marriage again and decided to marry her.

This Divine commandment meant that no longer could Muslims regard marriage to a divorcée a wrongful act. Also as Zaid(ra) was the Holy Prophet’s(saw) adopted son and was known as his son, by marrying Zaid’s ex-wife it was a practical demonstration to the Muslims that an adopted son is not the same as a biological real son. This resulted in the eradication of a custom of ignorance practised by the Arabs.

Now Ms Jones also invites the reader to speculate that at times the Holy Prophet’s(saw) revelation was ‘manufactured’ to suit the situation. To be fair, she is not alone in this. Other critics of Islam have made similar accusations with regard to the marriage of Hadhrat Zainab(ra) and they allege that when he became desirous of marriage to Hadhrat Zainab(ra) he sought the shelter of revelation in order to make it legitimate and to save himself from possible objections.

However, there are many incidents when the Holy Prophet(saw) received revelation that was not in accord with his wishes. An example is when the Holy Prophet(saw) led the funeral prayer of the leader of the hypocrites, ‘Abdullah Bin Ubayy Bin Salul, he then received the following revelation:

Never say prayer over any of them when he dies, nor stand by his grave to pray; for they disbelieved in Allah and His Messenger and died while they were disobedient. (Ch.9:V.84)

In like manner, when the number of his wives reached a figure which according to Allah’s knowledge was the appropriate limit, he was sent the revelation: ‘It is not allowed to thee to marry women after that…’. (Ch.33:V.53) Interestingly Ms Jones does not include this in her story.

It is a fallacy therefore to assume that the Holy Prophet(saw) used to manufacture revelations as and when it suited him.

The Jewel of Medina is replete with so many historical inaccuracies that it beggars the question as to how Ms Jones could claim that her book was well researched. One is also left wondering in what ways Ms Jones’ character ‘A’ishah could be considered to be a source of inspiration to Muslim women searching for empowerment from their male oppressors? Although she frets constantly at her husband’s marriages, apart from wanting to fight battles armed with her sword, Ms Jones’ ‘A’ishah seems to spend most of her time fretting at not being the centre of attention in her husband’s life. She seems to lack a real understanding of her husband’s Divine mission. Is this a heroine who can empower Muslim women or any women for that matter?

Ms Jones need have looked no further than at the true accounts of the lives of the wives of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(saw) who, each in their own right, were heroines. By becoming Muslims, they challenged their cultures’ view of the position of women in society. They became empowered through the Might of God and His teachings. No longer was the birth of a baby girl an event of shame and no longer were women the possessions of their male folk. Instead Islam instructed Muslims that; ‘the best of you are those who behave best towards their wives (and families)’ (Tirmidhi) and that ‘the best dinar (money) is that which a person spends on his wife and children’ (Sahih Muslim).

Through their marriages to the Prophet(saw) these Muslim heroines educated their men and women, about God’s message and thus ushered in a new world order. Although few in number, they suffered hardship and persecution in order to establish the religion of Islam and to lay down the foundations for a better world. Authors do not need to invent or embellish any details to tell their stories to the world, because the lives of these Muslim heroines are an example and an inspiration for all women of all faiths and ages.

Islam has never prevented debate and has always upheld freedom of speech. Like all other freedoms there has to be respect and dignity for the sentiments of others.

Let us conclude with Ms Jones’ own words:

‘Writing is, after all, a dialogue between the writer and the reader. How illuminating it would be for us all if the reader’s voice could be included in this conversation. Perhaps we might learn a few things – not only about Islam, but about one another.’ (Islam on line)

We sincerely hope that Ms Jones applies this advice to her own writing ambitions.

Add Comment